Technical Note

Reproducibility and tissue integrity: spatial biology without compromises

Posted on:

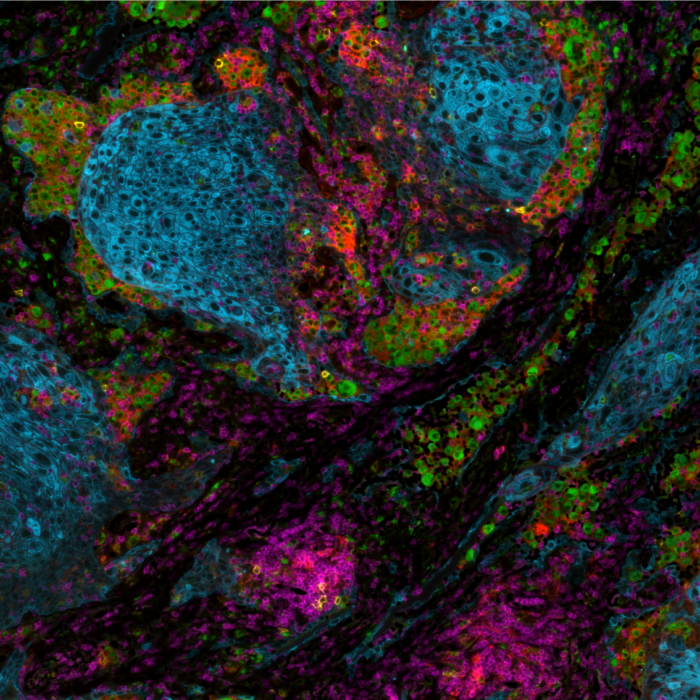

The rise of multiplex spatial biology

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is well-established in spatial biology research and diagnostics practices as a tool to assess tissue pathogenicity and potential therapies. One of its most popular techniques, immunofluorescence (IF), often used in tissue-based research, was once limited to labelling only one marker per tissue section1. However, since then, the need to further explore the tissue microenvironment in a multidimensional and interconnected manner has fueled multiple advances in IF applications. Presently, detection of two or more antigens on the same tissue is common and can be performed sequentially or simultaneously2. This is referred to as multiple labeling or multiplex IF (mIF)3. The use of quantitative multiplex analysis has spread through numerous research applications ranging from oncology, immunology, immunotherapy development, infectious diseases, neuroscience, and other pathological disease states4.

The bumpy road from multiplex to hyperplex spatial biology

Adoption of spatial biology applications is rapidly increasing, both in number and content depth. Fundamental discovery, as well as translational research laboratories, require the identification of an increasingly large number of markers on a single slide to obtain high-plex data, also known as hyperplex analysis. However, exsting and new technical approaches are required to overcome numerous technical challenges:

Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA)-based staining is one of the most classic approaches to mIF. It involves the detection of all markers on a tissue sample simultaneously. It is, therefore, limited by the number of microscope channels or, in some cases, the spectral unmixing capabilities available5. For this reason, TSA-based mIF is rarely used above 10-plex analysis.

Cyclic IF is another well-known multiplexing method that aims at breaking through this barrier: it consists of repeated cycles of single-plex or low-plex staining, using antibodies that are directly conjugated to a fluorophore, followed by imaging and signal removal steps on the same tissue slide, generating individual images that can later be stacked together forming a hyperplex image6. Nevertheless, cyclic IF does come with significant challenges:

- Issues with tissue preservation: cyclic IF methods that require multiple rounds of signal removal by deactivation or strip-off of fluorescently-labeled antibodies, can use acidic buffers, strong reducing agents, proteases, heating steps or antibody deactivation through chemical processes or photobleaching (Figure 2). These methods raise concerns around tissue preservation, reproducibility, and quality of results.

- Technical limitations in plex level: repeated harsh cycles of signal removal present a technical barrier in the number of cycles that can be performed and, therefore, in the maximum number of markers that can be simultaneously analyzed without significant damage to the tissue integrity.

- Limited to use with primary-conjugated antibodies: laboratories using cyclic IF typically need to develop new assay protocols from scratch. Not being able to leverage existing validated libraries of non-conjugated antibodies, can be very time-consuming, taking up weeks, or, most often, months. Moreover, the absence of secondary antibodies in this approach prevents the use of any amplification, and detection of low expressing markers can be challenging.

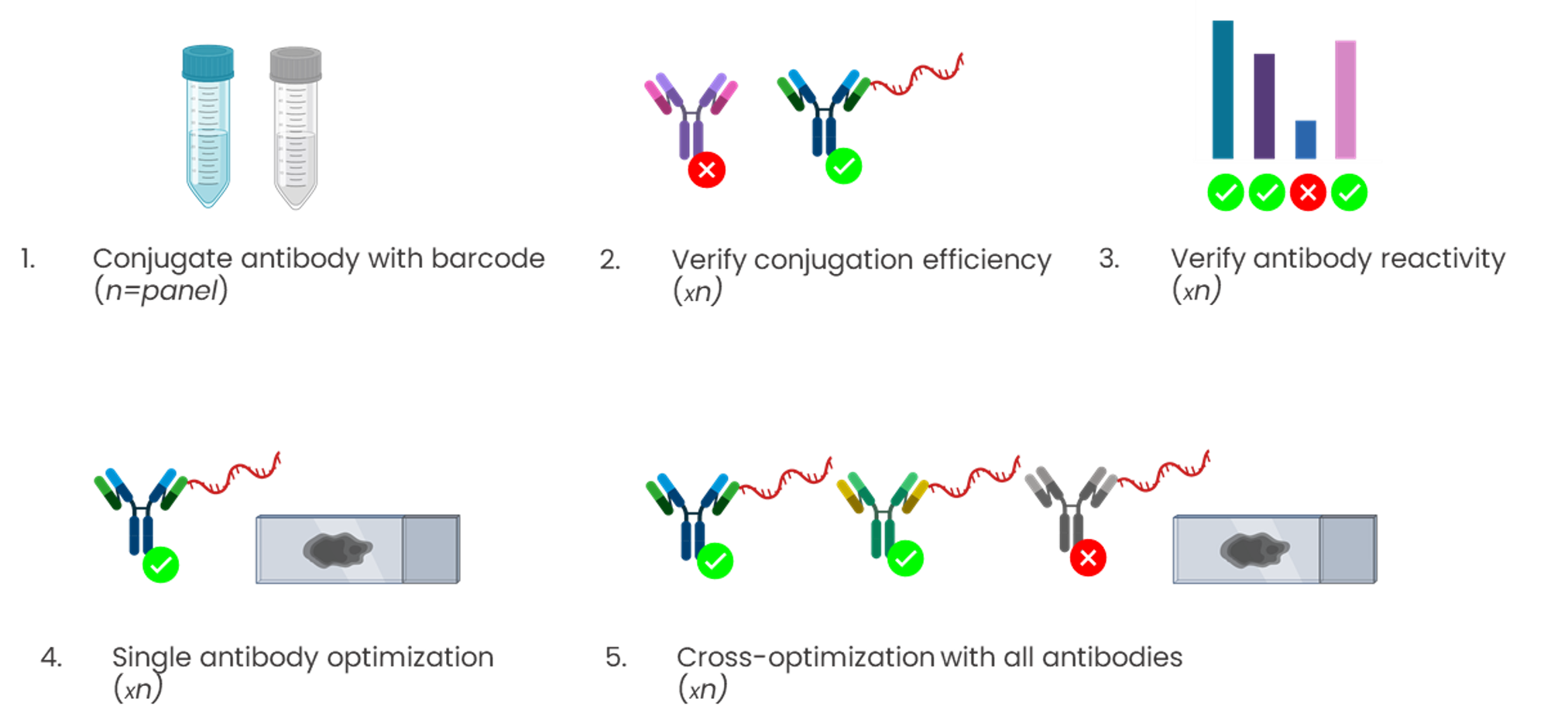

Conjugation-based approaches require highly manual, complex, and time-consuming upstream conjugations or barcoding of primary antibodies (Figure 3). These steps often come with high unwanted variability, dramatically affecting the assay reproducibility, and conjugations themselves have a potential failure rate of up to 75%.

Related Articles

Assay development: how to overcome the challenges of TSA-based mIHC assays

Posted on 11 Oct 2022

Read Post