Spatial Biology Education

Spatial proteomics: six barriers to multiplex immunofluorescence marker optimization and how to overcome them

Posted on:

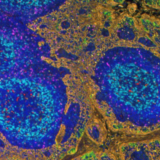

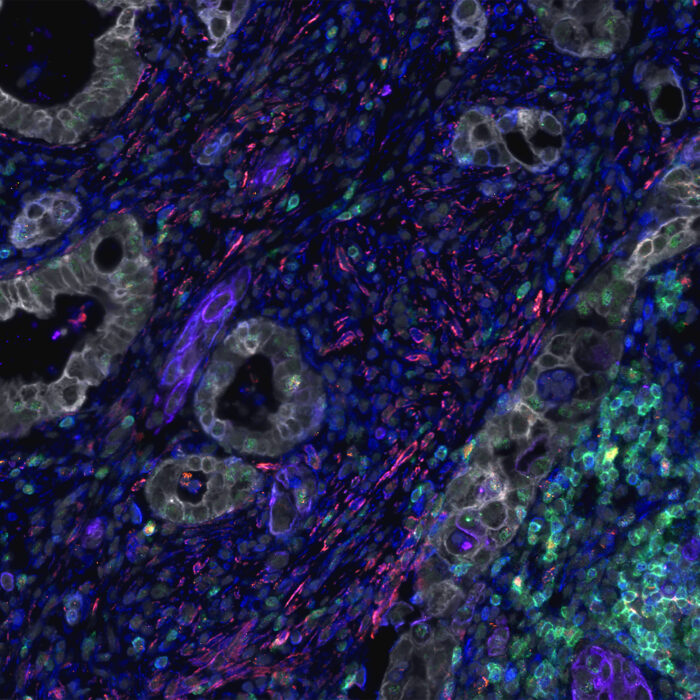

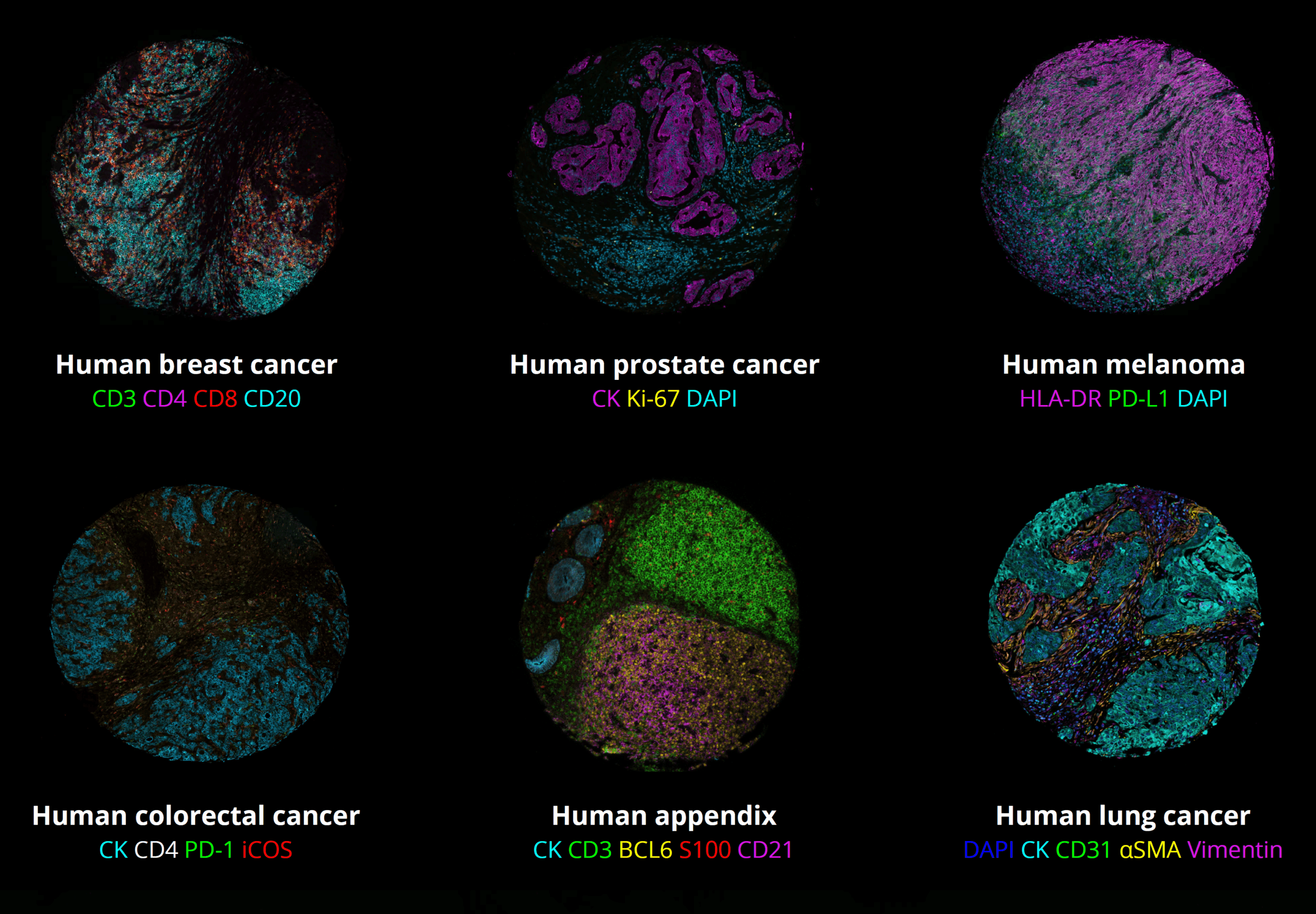

At the end of 2024, Nature named spatial proteomics as its ‘method of the year’ for its critical role in exploring and mapping biological complexity1. Spatial proteomics is the study of proteins within their spatial context in tissues. The term covers a broad swath of immunohistochemistry-based methods that can be used to generate multiplex images of specimens. These multiplex images are datasets with spatial information of protein distribution in the tissue, where dozens of proteins can be analysed simultaneously (Figure 1). Any researcher planning to incorporate spatial proteomics into their work must begin by carefully selecting a platform that aligns with their specific research goals. The success of any spatial biology program fundamentally depends on reliable and consistent biomarker detection. Without this critical foundation, the accuracy of spatial data is at risk, potentially resulting in incomplete or misleading biological interpretations. Optimizing the use of antibody markers in the process is therefore vital. Marker optimization involves identifying, selecting, and improving assay conditions to ensure accurate detection of protein markers within a tissue sample. This has knock-on effects on the rest of the imaging process, and can affect the speed, reproducibility and accuracy of an experiment, which in turn will affect downstream image and data analysis, including data quality and robustness. Therefore, spending time on optimization is essential to developing robust panel, data and spatial biomarkers, especially in personalized medicine.

There are several challenges to achieving successful marker optimization within high-multiplex imaging, and current methods often require extensive time, resources, and investment. This can make spatial proteomics programs slower and more resource-intensive than they need to be. The good news for researchers is that innovative new methodologies are emerging to solve these issues – ensuring that spatial proteomics can be as simple, fast, and reliable as possible. Let’s review some challenges and their solutions.

Challenge 1: lack of panel flexibility

Typically, spatial proteomics platforms use fixed, pre-defined antibody panels, meaning that the selection of antibody markers used in these platforms is already decided and standardized by the manufacturer, and researchers cannot add their own antibodies to the panel. This makes it difficult for researchers to make simple adjustments to their experiments on the fly without losing data integrity. Sequential immunofluorescence (seqIF™) technology, developed by Lunaphore Technologies, a Bio-Techne brand, is an emerging alternative to this approach, since it allows for the flexible sequential addition of markers, enabling the incorporation of any off-the-shelf antibody into the panel design (Figure 2). This more flexible approach means that researchers can incrementally adjust or expand panels as project needs evolve, reducing the need to start from scratch when adding or removing markers.

Challenge 2: spectral overlap

Spectral overlap can be a challenge in fluorescence-based assays. Spectral overlap occurs when the emission spectra of different fluorescent dyes used in imaging overlap with one another. If the emission spectra of two or more fluorophores are too close, their signals can become indistinguishable, making it difficult to accurately separate and quantify individual markers. Researchers need flexibility in choosing fluorophores that are best suited for the detection system they are using. One way to mitigate this challenge is to use a platform that performs iterative cycles of staining and imaging, with efficient antibody removal between each cycle. This method allows researchers to use a limited set of spectrally distinct fluorophores across multiple cycles, effectively eliminating concerns about spectral overlap.

Challenge 3: labor-intensive processes

Spatial proteomics workflows often involve several lengthy, manual, and thus error-prone steps. These labor-intensive processes not only increase hands-on time, but also create bottlenecks for researchers and certified research organizations, aiming to generate high-quality data efficiently and allocate resources appropriately. The need for manual intervention at multiple stages of the experimental workflow, slows down research progress and project throughput. It also makes reproducibility challenging to achieve, since the accumulation of variation will lead to high experimental variability, on top of the assay and tissue variabilities. Because of this, spatial biology platforms with the ability to automate processes, such as COMET™, have several advantages over platforms without this capability. Platforms like COMET™, can act with no user intervention, providing walk-away automation on even the most complex elements of spatial proteomics. By using standardized protocols and controlled experimental conditions, automation can aid marker optimization by minimizing batch-to-batch variability.

Related Articles

The Spatial Biology Week™ 2022: the transforming power of spatial biology

Posted on 07 Nov 2022

Read PostAssay development: how to overcome the challenges of TSA-based mIHC assays

Posted on 11 Oct 2022

Read Post